Update: Filipinos in Liverpool (Part 2)

In response to the open call for

information on the Dela Crus vamily in Liverpool, I received a letter

from John DeLa Cruz. He wrote:

"I came across your website when I typed my surnamejust from curiosity. My name is John de la Cruz, great grandson of the John De La Cruz of 27 Frederick Street, Liverpool, mentioned in the 1881 census. I realize that your main concern is creating a history for Filipinos in the USA, and this is admirable. Equally, Filipinos have contributed to the economy and culture of the UK for well over 100 years, albeait without any recognition. Indeed, most British people think that Filipino sailors are a cheap and less effective alternative to the experienced British sailor with his long historical tradition. Little do they know of the greater tradition of seamanship associated with the Phillippines and its people. The British are also proud of their role in the two World Wars in Europe. Again, they do not realize the contribution and sacrifice made by Filipinos and their descendants in those conflicts. I have discoverd at least three sons of the Filipinos on your Livepool pages who made the ultimate sacrifice in World War One."

I also just got an email from the grandchildren of Juan Sarong, another early Filipino sailor (Ignacio family) in Liverpool. I only got started on this project when I was tracing Rizal's trip to Liverpool in 1888. These contributions enhance our history and I continue to receive documents and stories. I am hoping to find out what happened to the De La Cruz sisters who immigrated to New York. There must be hundreed of single boarders who might just be lost on this planet.

I would also like to give credit to the Scottie Press (Ron Formby), Liverpool Echo, Mersey Radio (BBC) and other online resources that have made it easier to connect all the dots.

I'd also like to give thanks to Anita Weldon and Steve whom I only know from an email address. Both have provided even more names and descriptions of Frederick Street. There is not much there now, as the area never recovered from the fury of Hitler's bombs. Liverpool suffered the sam German aerial bombardment as London. Fredicrick Street is known asthe site of the first public wash house (Laundry and Bathhouse) in Liverpool. It served as a busy meeting place.

John De La Cruz was generous enough to share his stories and research with us. Below is his account:

Before I recount the tale of the

de la Cruz family in Liverpool, I shall tell you a little about myself.

My name is John de la Cruz. I suppose if I were to use the style

of the Americans, I would be called John de la Cruz IV. I think

it best if we continue in this style, as we will discover later on.

I was born in Liverpool, Lancashire, England, in 1947. My father,

Francis de la Cruz (or Delacruz as it was then spelt, but I am trying

to return it to its original Spanish form) was born in Cardiff, South

Wales. My mother, Louisa Edwards, was born in Liverpool.

My interest in family research really began in the early 1970’s.

Up until then I was aware that my surname was Spanish in origin.

My father often told me that the family had originally come to Britain

from the Philippines, a former Spanish colony. But that was the

extent of my knowledge and I believed that that was the total.

Nothing else was to be known or discovered as most of the old

folk who knew the truth were long dead, and their memories and tradition

had gone with them. It took a casual comment from a complete

stranger to kick-start my journey back in time. In doing

so I discovered some amazing and tragic stories.

![]()

“I began my search for my ancestors in the William

Brown Library, which

houses many of Liverpool’s old archives. My grandfathers

name was

John de la Cruz (II) but I did not know his father’s name."

![]()

In 1971 I was

working in the Post Office in Liverpool and sat down at a table

in the staff canteen with some of my colleagues and a stranger, a lady.

I was introduced to her and she told me that she had lived in Frederick

Street years before and knew the de la Cruz family. I was suitably

impressed but, as I did not realise until many years later, we should

always make notes at the time or as soon as possible afterwards, with

a subject as important as family history. One thing I did

remember her saying was that there was a de la Cruz commemorated on

the World War I Role of Honour in the Town Hall in Liverpool.

I was keen to see that but as Liverpool Town Hall only opened to the

public once every year in those days I had to wait almost 10 months

see the commemoration.

I began my search for my ancestors in the William Brown Library, which

houses many of Liverpool’s old archives. My grandfathers

name was John de la Cruz (II) but I did not know his father’s

name. My first search was in Gore’s Street Directory, starting

with the most recent one and working backwards. Gore’s

were similar in format to telephone books that we have today.

They listed the houses in each street, gave the name of the head of

the household and his or her occupation. The following is

a list from my original notes from 1972. The name spellings are

all as found in the directories.

| Year | Name | Address | Occupation |

| 1873 | Eustagnio DeLacruz | 26 Drury Lane | |

| 1874 | Eustaquio DeLacruz | 24 Drury Lane | |

| 1875-1880 | Eustakew Delacruz | 20 Argyle Street | |

| 1889 | Eustaquie De LaCruz | 15 Frederick St | |

| 1890 | Philip Delacruz | 12 Frederick St. | Fireman |

| 1900 | Philip Delacruz | 12 Frederick St. | Mariner |

| 1900 | John Delacruz | 18 Frederick St. | Ship Steward |

| 1900 | Eustaquie Delacruz | 25 Frederick St. | Boarding House Keeper |

| 1909 - 1913 | Mrs Eustaquio Delacruz | 25 Frederick St. | |

| 1913 | Nicholas Delacruz | 9 Nova Scotia | Compositor |

| 1921 | Mrs. Annie Delacruz | 10 Frederick St. |

From this evidence it would appear that

Eustaquio was the first de la Cruz recorded in Liverpool.

However, it has to be pointed out that as I am only a part-time genealogist,

I have not by any means exhausted all possible sources for information

and I am sure there must be earlier documentary evidence.

However, the 1881 Census for 27 Frederick Street shows Elizabeth Delacruz,

sailor’s wife, aged 28, born in Liverpool. Elizabeth’s

maiden name was Winn. Although she was born in Liverpool,

I understand her family came from Hastings, Sussex, England.

Her father being a Master Sailmaker in the Royal Navy, a post akin to

Chief Engineer on ships today. Family tradition (gossip) has it

that her father strongly disapproved of her liaison with a foreigner

and disowned her.

Her eldest child, Francis is stated as being 10 years old so she would

have been barely 18 years old when she bore him. Josephina

is 7, John is 5 and Madeline is 2. All born in Liverpool.

I know for certain that this is my branch of the de la Cruz clan.

Firstly, John is my grandfather, John de la Cruz II.

I have early childhood memories of Auntie Fina (Josephina). I

remember that she had a parrot which bit my finger when I tried to stroke

it! I recall my father telling me that his Uncle Francis went

to live in South Africa in the 1920’s. Because of South

Africa’s strict race laws he changed his surname to Winn, his

mother’s maiden name. Family tradition says that he went

on to become the harbourmaster at Durban, South Africa.

I have still to verify this.

Also in the 1881 census I found the following people at 49 Upper Frederick

Street, No. 3 court, No. 3. Jane Delacruz, sailor’s wife,

46 years old, born Ireland.

No. 5 court, No. 3, Philip De La Cruz, Head of household, sailor, aged

31, born Manilla. Mary De La Cruz, wife, 29 years, born

Liverpool.

No. 13 court, No. 2, Elizabeth F. Roza, charwoman, aged 38 and her children,

Rosalia F. Roza, Jose A F. Roza, Mateo F. Rosa, Catalino F. Roza, Torevia

F., Roza and Ambrocio F. Roza. This family

is particularly interesting for two reasons. First of all,

you will notice the “F.” after each name. This would

indicate that Roza is only part of the family name, and that something

has been omitted, probably by the census clerk to save time. This

style of having two family names, for example Rodriguez Morientes, is

clearly Spanish in form. It is tantalizing to anyone interested

in family history. The other reason for being interested

in this family is that they are possibly connected with my branch of

the de la Cruz family through marriage. I understand a daughter

of Josephina de la Cruz married a Rosa (Roza). If they are one and the

same Roza’s, then they are the parents of Lita Rosa, my father’s

cousin, who went on to become a famous singer during the 1950’s

and 60’s.

One major point to note about these census returns are the addresses.

The “courts” were a 19th century system of housing.

If you can imagine walking along Frederick Street in the 1880’s,

a stone’s throw away from the docks. It was a cobbled street,

littered with horse manure and rubbish thrown out by householders. The

smell of drains, gas lamps, rotting litter and manure and coal

fires would assail your nostrils. The front doors and windows

of grubby, three storied terraced houses would glare down at you.

You would hear a myriad of strange languages and see people of many

nationalities.

Occasionally, there would be an alleyway set into a terrace of houses

Walking down this alleyway you would come to a court, a small square

surrounded by cramped, overcrowded dwellings which were part of the

main house or built separately at the back. The court itself

would be strewn with ashes from the coal fires and the detritus of everyday

living. In most courts there would be a pump at which drinking

water could be obtained. I’ll wager a “modern”

person wouldn’t drink it! There would also be a communal

toilet. Barefoot children would run around playing or scavenging

in the rubbish heaps. Dirt, disease and abject poverty were

commonplace. These were the conditions that our Liverpool ancestors

lived in.

To return to John de la Cruz I and his wife Elizabeth. They

had other children after the 1881 census was taken. In all, their

family consisted of : Francis, Josephina, John, Madeline, Johanna,

Benjamin and Henry. John de la Cruz I was shown as aged

40 in 1891. This means that he was born around 1851. He

was stated as being aged 62 when he died in 1911. From this evidence

I think we can discount the John De La Cruz, aged 34 years, on board

the vessel MAUORA in East Ham in 1881. How do I know that

John de la Cruz I was 62 when he died? I shall tell you.

As I stated earlier, I did not know my great-grandfather’s nor

my great-grandmother’s names nor precisely where they came from.

For a long time, I thought Eustaquio was my great-grandfather.

However, when I was researching in the early 1980’s I was in touch

with my uncle John, whom we shall call John de la Cruz III, he sent

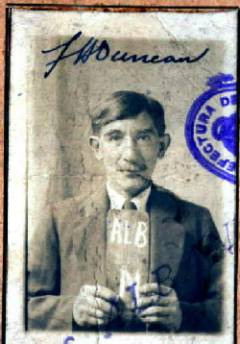

me my grandfather’s Argentine Immigration Regulations passbook.

Apparently this was a sort of passport which British seamen had to carry

to enable them to go ashore in Argentina. It was issued in 1926

and he was said to be 50 years old. So his stated age of

5 in the 1881 census isn’t too far out. More importantly,

it stated that his father’s name was John and his mother’s

name was Elizabeth. Further enquiries with the UK

Registrar of Shipping and Seamen revealed that his father was from the

Philippines. That is all I know of John de la Cruz I.

Well not exactly all. I do know how he died.

The only knowledge any of the family had about John de la Cruz I was

that he was “lost at sea”. I had to accept that it

would probably take me years to find out the truth. Well it did.

However, in 1999, I was talking to my oldest surviving relative, Ben

May, (his mother was Madeline de la Cruz), he is now aged 90 and a cousin

of my father. He said that John de la Cruz I was drowned

off the Island of Islay, Scotland, in 1911, the year that he was born.

This was a tremendous breakthrough. I made further enquiries with

the Museum of Islay life and discovered the following tragic story.

On the 1st November 1911, the sailing ship OCEAN left Dublin, Ireland, in ballast bound forNorway. There was a crew of fifteen, including the ship’s cook, John de la Cruz I. She sailed north up the Irish Sea and hit a violent storm. On 3rd November, off the West coast of Islay, her sails were blown away and she drifted uncontrollably towards Islay’s rocky shore.

Very early on the morning of the 4th,

two Islay men, Andrew Stevenson and Donald Ferguson saw the crippled

ship drifting and followed her as she was pushed northwards by the storm,

closer and closer to the rocks. The crew were huddled together

in the bow, unable to steer the ship without her sails. All they

could do was wait for the ship to hit the shore and pray for a chance

to save themselves.

The OCEAN finally went ashore, bow first on a rocky promontory just

north of Kilchiaran Bay on Islay’s rugged west coast. Before

the crew could jump ashore, gigantic seas swept her round and pushed

her stern first onto the rocks. With this second blow, the

ship broke in two. The crew were left in a perilous situation

as the ship looked as if it would break up at any moment. The

courageous captain, A. Christopher, jumped into the raging sea with

a rope and swam towards the shore. He only made it a short distance

when, sadly, he was smashed against the rocks and killed. They

crew members, wet and freezing, were left to wonder what was going to

happen next. Fate then came to their rescue. The stern mast

came crashing down and landed on the rocks. The crew immediately

seized their chance and scrambled down to the rocks. Two

men were swept off the mast and drowned. Twelve others saved themselves,

aided by the two brave Islay men who had by now roped themselves to

shore and swam out to assist the crew to safety.

The last crewman, an old man, was seen to sit on the stern hatchway

for four hours while the stormy sea raged and crashed over him, but

he would not, or could not move to save himself. Eventually he

disappeared below and was never seen again. By 2 pm on the 4th

November 1911 the ship had been smashed to pieces.

I obtained the following document a few months ago which confirms the

death of John de la Cruz I at Kilcherean on 4th November 1911.

It also gives his age as 62 and his address as Frederick Street, Liverpool.

Whether he was the old man who sat on the stern for four hours, or one

of the two swept off the mast I do not yet know. But my search

for information continues.

As I mentioned earlier, before discovering

this story I knew nothing about my great-grandfather. At

the time I read the tragic circumstances surrounding his death I was

overcome with a great feeling of sadness and personal loss which I cannot

fully explain. I intend to go to Islay sometime soon to pay my

respects.

The next major event to affect the de la Cruz family in Liverpool was

the outbreak of war in 1914. Some time after the war started,

I don’t know precisely when, the late John de la Cruz I’s

son, Henry, who was born about 1896, enlisted in the 6th Battalion,

Royal Irish Fusiliers. When I saw this fact I immediately asked

myself why an Englishman would join an Irish regiment. The

answer could be as simple as this. John de la Cruz I, a Filipino,

would probably be a Catholic by religion, and presumably so would hischildren.

If Henry de la Cruz had declared his religion as Catholic to the Army

Enlistment Officer, he would automatically been put in an Irish regiment.

It was a peculiar tradition in the British Army until well into the

1930’s that any Englishman declaring to be a Catholic was put

into an Irish regiment. We know little else about Henry, except

that he was the youngest son. However, from contemporary documents,

we can trace the regiment as it embarked on one of the most disastrous

campaigns in military history.

In November 1914, Turkey declared itself on the side of Germany in the

war. Turkey became a threat to it’s close neighbour, Russia,

Britain’s ally. Russia pleaded with their allies to

relieve Turkish pressure on their southern flank. The Allies decided

to land troops on the Gallipoli peninsula in Turkey. On 25th April

1915, a mixed force of British, French, Australians and New Zealanders

landed at Gallipoli. The whole thing became a terrible slaughter with

the Australian and New Zealand forces (the ANZAC’s) holding doggedly

onto a tiny cove. The Turkish forces, led by a German general,

would not give ground. A decision was made to land at Suvla Bay,

further up the coast to relieve the pressure on the ANZAC bridgehead.

This landing was made on 7th August 1915 at Suvla Bay, Gallipoli.

Part of the invasion force was the 10th (Irish) Division, which included

the 6th Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers. The Turkish artillery

shelled the men as they came ashore, causing some casualities, but the

Turkish infantry were retreating across the Anafarta Plain. Henry de

la Cruz, in the 6th Battalion, was part of the first advance inland.

They had to march around a salt lake to reach their objectives and then

come on to some hills from the northwest. They started at noon

and the day was very hot. As soon as the soldiers appeared on the beach,

the Turks began to shell them with shrapnel. They were still under

heavy fire when they turned the corner of the Salt Lake and sank up

to their knees in a morass.

By 5 pm the men, though very weary, were within 300 yards of their objective,

Chocolate Hill. They rested while the hills were shelled by allied

artillery and warships. At 7 pm, just before darkness fell, the

6th batallion and others, bayonets fixed, charged up Chocolate Hill

and drove the Turks from their trenches and an hour later were on the

crest of the hill.

All through the night of the 7th and into the morning of the 8th August,

the men worked busily to regroup themselves into their battalions.

Supplies of food, water and ammunition began to arrive, though many

men got no water until late on the 8th: their first drink in 24 hours.

Other units captured Kiretch Tepe Sirt and the area was secured.

During the next week the troops encountered fierce rifle fire and shelling

from the Turks. They also had to endure the excessive heat, and

the torment of thousands of flies. They lived on rations of bully

beef and hard biscuits. But worst of all, water was extremely

scarce. To make matters worse, dysentery began to spread amongst

the soldiers. The men were allowed a brief rest on the beach.

They risked being shelled to bathe in the sea and had their first shave

in several days; and welcome reinforcements appeared.

The 10th Division was next ordered to attack the Turks on Kiretch Tepe

Sirt, only parts of which had been captured by the British forces.

The ridge rose some 600 feet above sea-level, precipitous in places

and covered in thick scrub which seriously slowed down any movement.

The attack began on 15th August. The British advanced but were

met by a hail of machine-gun fire. By nightfall on the 15th they held

an uneven line below the crest of the hill and exposed to enemy fire.

The reserve battalions were called up and the 6th Battalion put on the

exposed eastern flank. They had just got into position when the Turks

crawled over the ridge in the darkness and charged down upon them.

They were beaten off with the bayonet; but just before dawn they attacked

again, throwing many grenades. The 10th Division had exhausted

their own small supply of grenades, made from jam tins. Gallant

efforts were made to charge the crest of the hill but they were beaten

back. The survivors lay among the dead on the slopes, in

the searing heat, and were constantly bombed and shelled, but they refused

to give way to the Turks. The 6th Battalion, Royal Irish Fusiliers,

already depleted by their attacks on the 9th, were almost wiped out.

They lost 10 officers and 210 men, most of whom were reported ‘missing’.

The regimental diaries record that Private 13867, Henry Delacruz died

on the night of 15th August 1915. He was 19 years of age.

His name is included in the 27,000 British and Commonwealth troops,

recorded on the Helles Memorial at Gallipoli and who have no known grave.

He is also the de la Cruz that is commemorated on the Role of Honour

at Liverpool Town Hall. The Commonwealth War Graves Commission

commemoration, which is on the web on www.cwgc.org.uk gives the information

that he was the youngest son of John and Elizabeth Dela Cruz, of 13

Upper Pitt Street, Liverpool.

John and Elizabeth also had a son, Benjamin, shown as being aged 8 in

the 1891 census. He was a boot repairer by trade and was 23 when

he married Annie Swinchin, aged 19, on 26th January 1914. He enlisted

in the army after the start of World War I. He joined the King’s

Liverpool Regiment and his army number was 268286. My research

is incomplete so I cannot tell you anything about his campaigns with

the King’s. My dad’s cousin, Ben May, remembers him

well. He recalls him coming home on leave from the army

and promising to bring young Ben a horse next time he was home.

Ben recalls asking him about the horse a few months later , to be told

that the railway company would not let it leave the station!

Some time during World War I, we don’t know why or when, Benjamin

was transferred to the 2nd/7th Battalion, Lancashire Fusiliers.

I can only assume that his regiment, the King’s Liverpool, was

so badly depleted that men were transferred to others. It could

also be that the Lancashire Fusiliers were desperately short of experienced

soldiers and he was transferred because of that. I’m

sure the answer is available somewhere. I’ll have

to keep on searching.

On 31st July 1917, the British began a ‘Big Push’, a large

scale attack on a wide front, on the Ypres salient in Belgium.

The object was to secure the high ground to the north east, Passchendaele

Ridge, roughly six miles from Ypres. On 1st August it began to

rain, and rain and rain. It was to become the wettest August in

living memory. The ground had already been churned up by shellfire

from both sides, and the whole area became a slimy, slippery quagmire,

where thousands of men drowned in liquid mud.

I don’t know exactly where or how the 2nd/7th Battalion were involved

in the battle. We do know that by the middle of November,

after three and a half months of wet, bloody slogging, the British and

Commonwealth forces had managed the six miles to Passchendaele Ridge.

The regimental magazine for the Lancashire Fusiliers states that from

October 12th/November 8th the Battalion was employed in refitting and

receiving drafts. It may be during this period that Benjamin de

la Cruz joined them. From November 8th to 16th they were in the

line on Passchendaele Ridge. The battalion magazine records

that: “Heavy shelling and bad weather made this tour one of the

most arduous the Battalion ever experienced.” On Saturday

10th November 1917, Benjamin de la Cruz was killed in action.

He was 27 years old.

Private 64879, John De La Cruz, 4th Battalion, The King’s (Liverpool

Regiment), died on Wednesday 26th September 1917, also in the Ypres

salient. He was 19 years of age. His name, and Benjamin’s,

are two of 34,927 British and Commonwealth soldiers who died between

August 1917 and the end of the war in November 1918, and who have no

known grave. They are commemorated on panels at the back of Tyne Cot

cemetery, close to Passchendaele in Belgium.

John De La Cruz was the son of

Isabella De La Cruz, of 20 Liver Stret, Liverpool, and the late Domingo

De La Cruz.

Nicholas De La Cruz was the son of Philip and Sarah Anne De La Cruz,

12 Frederick Street, Liverpool. He was married to Janet.

In the 1913 Gore’s Directory he is shown as living at No. 9 Nova

Scotia, Liverpool, and his trade was a Compositor. Nova Scotia

was a small street on Mann Island, Liverpool, where the famous Liver

Buildings now stand. During World War I, Nicholas also enlisted

in the army. He was Private 24479, of 20th Battalion, the King’s

(Liverpool Regiment).

Throughout 1915 and 1916 the British Army was being reformed and rebuilt

because of the losses sustained to its professional soldiers when the

Germans invaded France and Belgium in late 1914. Lord Kitchener,

who was in charge of the army, came up with the idea of recruiting ‘Pals

Battalions’, where men from the same area, or indeed, even

from the same occupation, would serve together in the army. It

was hoped that this would provide a coherent and well disciplined body

of men. The 20th Battalion, The King’s (Liverpool

Regiment) was one of those which recruited in the city centre of Liverpool.

I know nothing else of Nicholas’ army career except the following.

On 1st July 1916, the 20th Battalion were part of III Corps, 30th

Division, 89 Brigade of the British Army which took part in the attack

in the Somme department of France in order to relieve pressure on the

French Army who were being decimated at Verdun. In the first attack

on 1st July, on a 16 mile long front, the British army suffered

almost 60,000 men killed, wounded or missing. It was the worst

single day in the history of the British Army. The horror of that

one day effected almost every town and village of the Pals Battalions

of the Midlands, the North and West of England. A single column

of these men, spaced at arm’s length would stretch 30 miles.

To read out their names would take two weeks.

The intention of this ‘Big Push’ was to advance from a point

near Albert to Bapaume, a distance of some 16 miles. They

never made it. By 17th November 1916 they had got just over halfway.

The only real success of day was made in the south of the line,

where the 17th, 18th, 19th and 20th Battalions, King’s (Liverpool

Regiment), the Liverpool Pals, and the Manchester Pals, supporting the

French Sixth Army, captured and held the village of Montauban.

On 30th July, the 20th King’s were part of an attack at 4.45 am

from trenches south of Trones Wood, near Montauban. The 20th took

the German front line and reached the Hardecourt-Guillemont road.

Later in the day, believing themselves to be cut off, they pulled back.

It was at some time during that day that Nicholas De La Cruz was killed,

aged 27. His name, along with over 73,000 other British and South

African men who have no known grave, is commemorated on the Thiepval

Memorial. The memorial, which is 140 feet high, is the largest

British war memorial in the world.

|

If we can assume that the second

generation Filipino community in Liverpool numbered 100 or so, then

the sacrifice of these young men in percentage terms was greater

than many other communities in the UK and Ireland. Of

course, they are the only four that we are aware of. There

may be many others. A poignant footnote to the deaths of these gallant soldiers, and also the death in a shipwreck of John de la Cruz I. My dad’s cousin, Ben May, recalls that he was brought up in a household full of women. There were no men. They were either at sea on ships, or dead. Strangely, he remembers that these women spoke nothing but Spanish at home. Remember, they were all born in Liverpool. Does the fact that they spoke Spanish give us a clue as to where John de la Cruz I came from in the Philippines? |

| When war broke out in 1914, my grandfather, John de la Cruz II was 38 years of age, too old for military service. He was a Merchant seaman, having run away to sea when he was 13, so family tradition has it. According to the UK Department of Trade’s limited records, he served in the Merchant Navy as a Cook at least from 1915 to 1939, making 33 voyages between 23rd December 1918 and 26th August 1939. | |

On 27th June 1924, another Hudson’s Bay Company vessel, the schooner LADY KINDERSLEY, set sail from Vancouver to Point Barrow in Alaska. The ship had auxiliary power but a bearing kept burning out, which meant the ship had to proceed most of the way by sail power. Eventually the engine was repaired and the ship continued to Point Barrow, 11 days late. When she finally reached Barrow, she was stopped from proceeding further by ice. The captain moored his ship to the shore ice to prevent her being carried away by strong currents. In the morning they discovered that the shore ice had broken away and the vessel was now moored to a floating ice field. |

|

They also discovered that the pressure of the ice had severely damaged the rudder. Eventually, the vessel became stuck fast in masses of ice floes. The same ice pack crushed an American vessel, the ARCTIC but all crew managed to escape safely.

The captain of the ARCTIC immediately

began to organise a team to rescue the crew of the LADY KINDERSLEY.

Meanwhile, the Hudson’s Bay Company had diverted the BAYCHIMO

to go to the assistance of the stricken schooner, but it would be another

two weeks before the slow steamer could reach the scene of the disaster.

By 21st August the LADY KINDERSLEY was so badly crushed in the Arctic

ice that the captain gave the order to abandon ship. After a perilous

journey across packed ice, with steep ice cliffs and deep holes, they

made it to a US ship the BOXER, which took them to shore at Barrow.

Part of the crew were transferred to a vessel which took them to Nome

in Alaska. From there they reached Vancouver on a passenger liner.

The remainder of the crew were picked up from Barrow some weeks later

by the BAYCHIMO, my grandfather’s ship, which had bravely battled

northwards through the ice to reach the strickenschooner. Special

medals were struck and awarded to all who participated in the rescue.

My grandad’s medal still has has pride of place in my cousin’s

living room.

John de la Cruz II left the BAYCHIMO in 1924. From his Argentine

passbook we know that he made several voyages from the UK to the River

Plate from 1926 to 1939, when he had spent almost 40 years at sea.

I was told various tales about my grandfather. That he was in

Mexico during Pancho Villa’s revolution. There were

stories that he was involved in gun running to the Republican side in

the Spanish Civil War. This could be true. Apparently

a number of vessels sailed regularly from Cardiff to Northern Spain,

running through a blockade. I am in the process of investigating

this further.

I have almost come to the end of my story.

But, as Winston Churchill said: “it is not the beginning

of the end but the end of the beginning”. Who

knows what future research will reveal?

To return to Eustaquio de la Cruz. As I mentioned earlier,

for many years I thought he was my great-grandfather. During

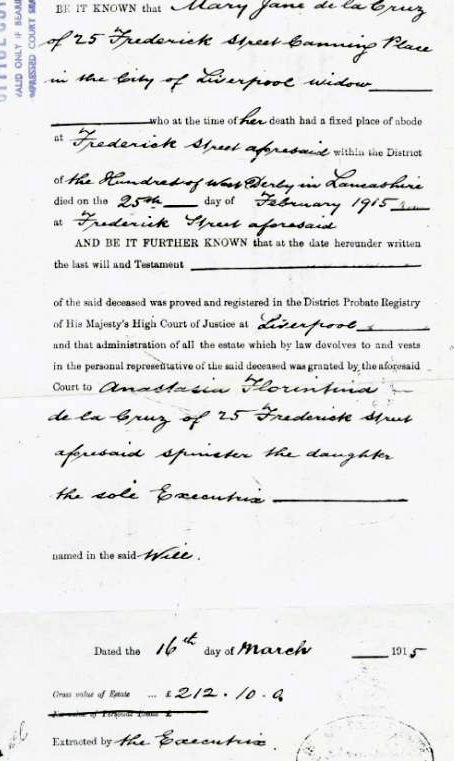

my research I obtained a copy of the Last Will and Testament of Mary

Jane de la Cruz, who we now believe to be the widow of Eustaquio.

Please see the following pages.

Further to this, my research on the 1891

census revealed the following.

21 Frederick Street.

Eustaquio De La Cruz, Head. Aged 56. Shipping agent. Born

Cuba, Isles de Filipina.

Mary, Wife, aged 41, Publican & Licensed Victualler, born Liverpool

Maria, daughter, 14, assistant to above, born Liverpool

Augustina, daughter, 10 assistant to above, born Liverpool

Isabella, daughter, 6, born Liverpool

Eustaquio, son, 4, born Liverpool

Anastasia, daughter, 2, born Liverpool

Alberto, son, 4 months, born Liverpool.

There is no mention of a Francesca Juliana. But, of course, this

does not mean she didn’t exist. It could mean she was at

a different address when the census was taken!

Finally, this time round. A coincidence. The details

that Ted and Nestor sent to me include the fact that there was a Francesca

de la Cruz. Well, a Francesca de la Cruz also exists today.

Here is a photograph of her taken on board the ferry from Santander,

in the North of Spain to Plymouth in 2001.

|

She is my 16-year-old daughter, whose full title is Maria Francesca de la Cruz, but she prefers Francesca. I named her after my late father, Francis. Note, that my father’s uncle was called Francis, and there was also a Francesca de la Cruz. As first names do carry on through many generations, could this be a link back to someone in thePhilippines? |

![]()